The fastest growing population group in the United States includes those people between age 65 and 70, with over 12 million people. With the aging baby boomers, the population age 65 and higher is expected to continue growing rapidly.

However, growth in the aged population has little to do with improved health habits. The Center for Disease Control reports that more than one-third of older adults aged 65 and over were obese in 2007-2010 with obesity prevalence was higher among those aged 65‒74. Studies regularly report that the aging population loses muscle, gains fat, and overall quality and quantity of life are impaired.

While at the same time there are many optimistic findings in medical research to support improved quality and quantity of life as we age. In his excitement over these developments, former President of the International Sports Science Association Frederick Hatfield wrote;

“We are now entering an exciting time when medical doctors, exercise physiologists, and gerontologists are all redefining what aging is. No longer should we expect to get sick, get heart disease, get Alzheimer’s disease or any other maladies commonly associated with the passing of time…the sunset years are beginning to see the light of a new day”

The solutions to improving the sunset years lie in exercise to enhance strength and cardiovascular endurance. Research now shows that through exercise you can add life to your years, and perhaps years to your life.

Add life to your years and years to your life.

Before we offer the solution, lets be clear about the problem as it is understood.

Use It or Lose It

As the population ages, the medical research community pours millions of dollars and hours into researching the physical effects of age. Dr. Walter M. Bortz, in his ground-breaking research in 1982 published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, concluded from his extensive study that disuse (the lack of use) was a key factor in the physical deterioration normally associated with aging.

Bortz’ analysis concluded that the “biologic changes commonly attributed to the process of aging demonstrates the close similarity of most of these to changes subsequent to a period of enforced physical inactivity.” Bortz offered a voice of encouragement for the health and fitness community:

“There is no drug in current or prospective use that holds as much promise for sustained health as a lifetime program of physical exercise.” Dr. Walter M. Bortz

Bortz would later write in his book We Live Too Short and Die Too Long that; “Almost everything we have been taught about aging is wrong. We now know that a very fit body of 70 can be the same as a moderately fit body of 30.”

Lost Motor Function

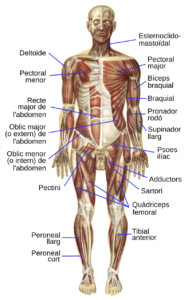

The term motor unit is used to describe the nerves, muscle fibers, tendons and ligaments together that make up a larger group. For example, the bicep motor unit would include not only the muscle tissue but also the tendons, ligaments, and nerves in the connecting joints, the elbow and shoulder. Studies of aging would suggest two prominent changes; (1) fast motor units fail with age, and (2) motor nerves disengage with age.

The term motor unit is used to describe the nerves, muscle fibers, tendons and ligaments together that make up a larger group. For example, the bicep motor unit would include not only the muscle tissue but also the tendons, ligaments, and nerves in the connecting joints, the elbow and shoulder. Studies of aging would suggest two prominent changes; (1) fast motor units fail with age, and (2) motor nerves disengage with age.

Fast Motor Units Fail. Muscles have fast and slow motor units. Quick powerful movements require large, fast motor units while slower movements for maintaining posture use smaller, slower motor unites. In examining older muscles, it appears that the slower motor units start to predominate, which makes powerful movements more difficult.

Motor Nerves Disengage. As people age, motor nerves (the nerves that turn on muscle figers) become disconnected from individual muscle figers – they develop “loose” connections between the nerves and muscles. Musclie physiologists estimate that by age 70 in most people, 15% of motor nerves have disengaged from their muscle figers. Strength training can retard much of this loss.

Lost Muscle Mass. As muscles are used less they shrink. According to one study, beginning at about age 50 the average untrained person loses 1% of muscle mass per year. By age 70, one can expect to have lost 25% of their younger muscle mass. Lost muscle mass has many negative consequences including; (a) strength decline, (b) reduced metabolism, (c) postural deterioration, (d) weakened resistance to injury, and (e) a negative impact to physical appearance.

In total, evidence from an aging population would tell us that Muscles become slower and less powerful with age. The negative side effects are many.

But medical research shows conclusively that this is not a necessary process. It can be retarded and even reversed with strength training.

Strength Training: Positive Impact

While we are growing older, and the community around us grows pale and ill, we can have hope that exercise and fitness is a component in the solutions to the adverse effects of age.

While we are growing older, and the community around us grows pale and ill, we can have hope that exercise and fitness is a component in the solutions to the adverse effects of age.

Only a decade or two ago, doctors told older adults to be wary of exercise and instead to embrace their rocking chairs. Today, experts agree that exercise improves your physical condition no matter what your age or circumstance. While we feel at times we are organizing new solutions for overall health and fitness, Dr. Alex Lief of Harvard Medical School reminds us that “regular daily physical activity has been a way of life for virtually every person who has reached the age of 100 in sound condition.”

Strength training, in the form of progressive resistance using dumbbells, barbells, or machines, is essential for building muscle, maintaining muscle, or minimizing muscle loss. In addition to muscular benefits, strength training also applies stress on the skeleton, which builds stronger more dense bones which are less likely to fracture during accidents. Strength also builds and maintains the muscles required for dynamic balance, helping reduce the incidence of accidents.

Study after study demonstrates that proper exercise, in addition to making us look and feel better, actually lengthens and improves the quality of our lives.

- Muscle Strength

- Bone Density

- Improved Lung Capacity

- Reduced Risk of Injury

- Physical Appearance

Regardless of your present age or circumstance, it’s never too late to start an exercise program including strength training. Whatever your starting point may be, you can transform your fitness at any age, along with your health, and appearance.

“The steadfast application of the combination of strength training, stretching, cardiovascular work, healthy nutrition, and a healthy lifestyle is the closest we can get to the fountain of youth” Stuart McRoberts

Every individual is unique. Someone who’s been exercising safely and effectively since he was a teenager may be in extraordinary condition when he is 65 years old, but it is impossible to expect he would have the same condition as at 30 years old. Likewise, if you’ve kept your body in condition from an active

The Program

Progressive Resistance. Strength training for the aging population should focus on low to moderate intensity with higher amounts of repetitions until you reach a good level of base strength. Increase weights on a periodic schedule as you are able while maintaining high repetitions in good form.

Cardiovascular Training, known simply as ‘cardio’, should be pursued to enhance the function of the lungs to supply oxygen-rich blood to the working muscle tissues and produce energy. Cardio could include

Frequency: A full workout, with strength training and cardio, should be completed two to three times per week.

Duration: Approximately 60 minutes total, with 30 minutes of strength training and 30 minutes of cardio.

Intensity: Low to moderate with heart rate training zone between 60% and 75% of maximum heart rate.

For those who are just beginning, a suitable beginning may include a full body dumbbell workout with light weights so that you can perform 4 sets of 12 repetitions for each exercise.

Regardless of your age, you should involve professionals in your fitness plans before beginning any exercise program. At a minimum, you should have a physician’s approval to exercise and the advice and support of a certified fitness trainer. Once your doctor’s approval is obtained, contact us for training support.

Resources:

Bortz, Walter M. “Disuse and Aging,” Journal of the American Medical Association. 1982;248(10):1203-1208.

Center for Disease Control. “Prevalence of Obesity Among Older Adults in the United States, 2007-2010“, www.cdc.gov, accessed March 6, 2018.

Fahey, Thomas. Strength and Conditioning, 3rd Edition. International Sports Science Association, Carpinteria. 2017.

Harvard Medical School, “Strength Training for All Ages,” Harvard Health Publishing, health.harvard.edu, accessed March 6, 2018.

Hatfield, Frederick. “Exercise and Older Adults” in Fitness: The Complete Guide, International Sports Science Association, Carpenteria. 2016.

McRoberts, Stuart. “The truth on age and exercise” in Build Muscle Lost Fat Look Great, CS Publishing, Connell. 2006: pp. 71-74.

United States Census. “2010 Census Shows 65 and Older Population Growing Faster Than Total U.S. Population“, www.census.gov, accessed March 6, 2018.